Knee Dislocation

This is a devastating injury associated with rupture of several principle ligament in the knee, a high risk of complications and usually very poor function in the knee forever more!

Diagnosis

Hx |

|

LOOK |

|

FEEL |

|

MOVE |

Exclude associated injuries |

XRAYS |

AP and Lateral views

Stress views

|

MRI |

Useful to support clinical diagnosis. Grading of ligament injuries unreliable. |

Angiogram |

|

Associated Injuries

The relative displacement of the bones causes traction on all the structures crossing the knee. A high index of suspicion is required, looking for vascular, neurological and combined injuries.

Vascular injury accounts for 5% of cases, either a transection, intimal tear or thrombosis. The pulses must be present and equal to the other side. ABI/API measurements of less than 0.90 are shown to have a 95% sensitivity and 97% specificity for arterial injury of consequence.

Peripheral nerve injury, occurs in 20% to 40% of cases with half of these palsies being permanent. Ischaemia may mimic neurological injury.

Extensor mechanism disruption indicates severe displacement of the joint and is associated with a particularly poor prognosis.

Fractures of the femoral condyle and tibial plateau may be associated with these injuries, especially if there was axial loading as part of the mechanism. The fragments are likely to carry intact capsulo-ligamentous attachments and rigid internal fixation is recommended.

Classification

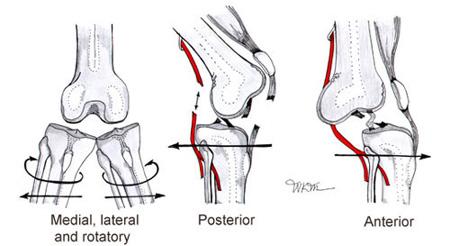

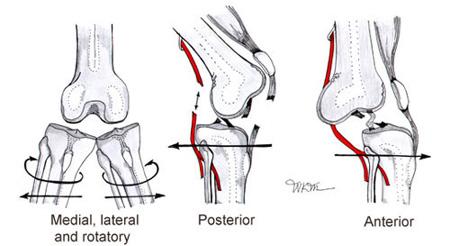

These injuries may be classified with reference to the direction of dislocation (i.e Which way the tibia is displaced wrt the femur)

Classification |

% |

Mechanism |

MCL |

PCL |

ACL |

PLC/LCL |

Anterior |

31 |

Hyperextension > 30 degrees |

Intact |

Ruptured (Occasionally spared) |

Ruptured |

Intact |

Posterior |

25 |

Posterior Translation - Dashboard/Bumper (Vascular injury most common) |

Ruptured |

Ruptured |

Ruptured |

Ruptured |

Lateral |

13 |

Ruptured |

Ruptured |

Ruptured |

Intact |

|

Medial |

3 |

Intact |

Ruptured |

Ruptured |

Ruptured |

|

Rotary |

4 |

Ruptured |

Ruptured (Occasionally spared) |

Ruptured (Occasionally spared) |

Ruptured |

There is also the "Anatomical Classification of Knee Dislocations" based upon the distribution of ligament damage.

Classification |

Subclass |

# |

MCL |

PCL |

ACL |

PLC/LCL |

KD-I |

No |

Intact |

Single Cruciate Ruptured |

Intact |

||

KD-II |

No |

Intact |

Bicruciate Injury Only |

Intact |

||

KD-III |

M |

No |

Ruptured |

Bicruciate Injury + |

Intact |

|

KD-III |

L |

No |

Intact |

Bicruciate Injury + |

Ruptured |

|

KD-IV |

No |

Full House of Principle Ligament Ruptures |

||||

KD-V |

1 |

Yes |

Intact |

Single Cruciate Ruptured |

Intact |

|

KD-V |

2 |

Yes |

Intact |

Bicruciate Injury Only |

Intact |

|

KD-V |

3M |

Yes |

Ruptured |

Bicruciate Injury + |

Intact |

|

KD-V |

3L |

Yes |

Intact |

Bicruciate Injury + |

Ruptured |

|

KD-V |

4 |

Yes |

Full House of Principle Ligament Ruptures |

|||

*Note there are additional annotations "C" for vascular injury and "N" for nerve injury.

Emergency Room Treatment

These injuries are often reduced by the paramedics and may appear relatively benign. A good history of the "mechanism of injury" is essential. These injuries are easy to miss.

Reduction should be undertaken immediately, before any other investigations, using simple sedation. Ischaemia of over 6 hours is associated with >80% rate of amputation. After reduction further assessment can be made. If a general anaesthetic has been administered then the opportunity for stress radiographs and EUA should be taken. Once reduced the knee should be immobilized in 20 degrees of flexion and neutral coronal alignment - this positioning should be recorded with a x-ray.

An irreducible knee dislocation usually occurs due to a button hole where the medial femoral condyle pushes through the capsule in the context of a lateral or posterolateral dislocation. Often a "dimple" forms overlying the medial aspect of the knee. An open reduction is required to replace the femur inside the capsular envelope.

Serial recording of perfusion and innervation must be documented before, during and after any manipulation. All of these patients must be admitted for observation and further management.

Specialist Treatment

Emergent interventions: Any vascular compromise must be investigated by means of angiography. After any vascular repair the limb should be protected from further damage by external fixation and fasciotomies. Those few open injuries requiring plastic surgical cover should be treated in a similar way.

An irreducible dislocation is best approached by an anterior incision and medial parapatella dissection. In the acute situation only limited repair/reconstruction is recommended.

All patients having an emergency surgery should have stress radiographs, an EUA, and compartment pressure measurements.

Elective reconstruction: There has been great debate about the timing and extent of ligament repair/reconstruction. In summary:

Experienced surgeons recommend operating in the 2-3 week window, after the initial swelling has settled and before all the tissues stick together in a fibrous mass. This window may be used to address all the reconstructions are for the first part of a staged approach - see foot note.

Nerve injury: The foot must be supported in a splint and specialist physiotherapy undertaken. If there is no improvement at 3 months then further investigation (EMG) and referral to a peripheral nerve injury unit is advised.

Foot note Mook et al recently did an interesting systematic review of studies to compare outcomes in early, delayed, and staged procedures as well as the subsequent rehabilitation protocols. Twenty-four retrospective studies were analyzed involving 396 knees dealing with multiple ligament knee injuries involving both cruciates and either or both collaterals. Data were compared as follows: 1) acute (time to surgery <3 weeks), 2) chronic (time to surgery >3 weeks), and 3) staged treatment (combination of repair and reconstruction in the acute and chronic periods). Findings were as follows:

Clinical Implications From a rehab standpoint, researchers found that those managed acutely with early mobilization had better outcomes as well as less range of motion losses. Observations from the researchers include a few important points. Reconstruction within three weeks after injury results in more anterior instability, more severe ROM complications, and more need for MUA. Secondly, they found patients that are managed in stages had the highest percentage of excellent/good subjective outcomes and the least ROM deficits. Third, although final ROM was preserved best in patients undergoing staged treatment, a high percentage needed follow-up surgery due to arthrofibrosis. This finding suggests that simultaneous repair and reconstruction of the cruciates acutely may lead to substantial ROM deficits and are unresponsive to follow-up surgery. Next, aggressive rehabilitation with early mobilization is associated with less ROM complications and earlier return to work, particularly in those who are acutely managed. In conclusion, researchers stated:

1. Mook WR, Miller MD, Diduch DR, Hertel J, Boachie-Adjei Y, & Hart JM (2009). Multiple-ligament knee injuries: a systematic review of the timing of operative intervention and postoperative rehabilitation. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 91 (12), 2946-57 PMID: 19952260 |

© Mr Gavin Holt :: CotswoldClinics.com :: Print this frame