The genitofemoral nerve or its branches (genital or femoral branches) can be entrapped anywhere throughout its course. Direct nerve injury occurs most commonly as a complication of lower abdominal surgery.

Anatomy

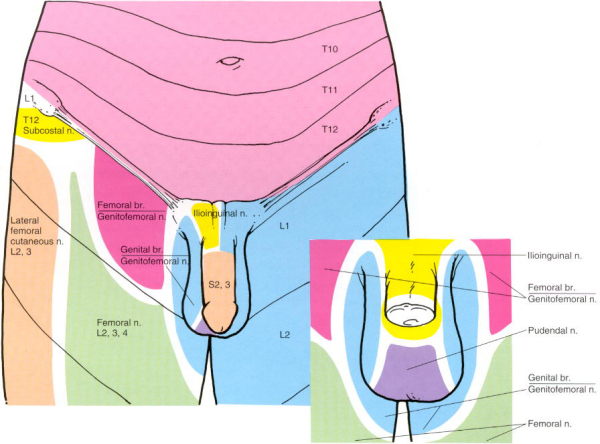

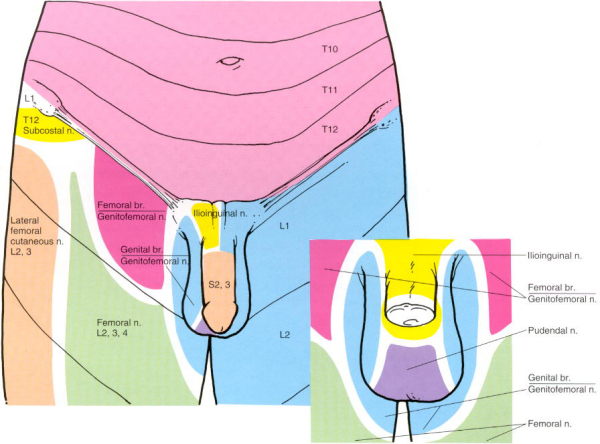

The genitofemoral nerve arises from the L1 and L2 ventral primary rami, which fuse in the psoas muscle. The nerve then pierces the anterior surface of the psoas major muscle at the level of L3-4 and descends on the fascial surface of the psoas major muscle past the ureter. It then splits into the genital and femoral branches near the inguinal ligament.

The genital branch continues along the psoas major to the deep inguinal ring and enters the inguinal canal. It supplies the cremaster muscle, spermatic cord, scrotum, and adjacent thigh in males. In females, it travels with the round ligament of the uterus and provides cutaneous sensation to the labia majora and adjacent thigh.

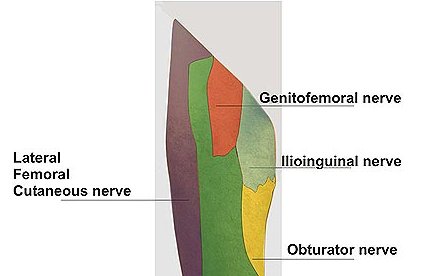

The femoral branch lies lateral to the genital on the psoas major and travels lateral to the femoral artery and posterior to the inguinal ligament to enter the proximal thigh. There, it pierces the sartorius muscle distal to the inguinal ligament and supplies the proximal portion of the thigh about the femoral triangle just lateral to the skin that is innervated by the ilioinguinal nerve.

Aetiology

Direct nerve injury may result from hernia repair, appendectomy, biopsies, and cesarean delivery. Indirect injury may also result from trauma to the posterior abdominal wall e.g. pregnancy, retroperitoneal hematoma. Fortunately, injury to this nerve is rare, even with open herniorrhaphy.

Symptoms

Injury to the femoral branch causes hypoesthesia over the anterior thigh below the inguinal ligament, which is how it is distinguished from the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerve. Groin pain is a common presentation of neuralgia from nerve injury or entrapment. The pain may be worse with internal or external rotation of the hip, prolonged walking, or even with light touch. Differential diagnoses include injury to the ilioinguinal nerve as well as L1-2 radiculopathies. Some anatomic overlap may exist with the supply of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves, which makes the diagnosis somewhat difficult to establish.

Unfortunately, no reliable electrodiagnostic test exists that can be used for diagnosis of injury to this nerve. Diagnosis typically is made using anesthetic nerve blocks: injection of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves anteriorly should leave the pain or abnormal sensation unchanged. Then a block of the L1 and L2 roots should result in relief. This should help to determine the diagnosis and to prevent unnecessary surgical exploration of an uninjured nerve.

Treatment

The above-mentioned blocks are diagnostic and therapeutic. Avoidance of aggravating activities should be emphasized. Membrane stabilizing medication may help the neuralgia (gabapentin, amitriptyline). Other medications include capsaicin cream, topical lidocaine patches, NSAIDs, or, possibly, tramadol. A trial with a TENS unit may also be beneficial.

If conservative treatment fails, surgical excision of the nerve is the treatment of choice. Some authors describe a transabdominal approach to the nerve (Magee and Lyon) with satisfactory results. The complications of this procedure include hypoesthesia of the scrotum or labium majus and of the skin over the femoral triangle, as well as loss of the cremasteric reflex. This usually will not result in notable morbidity. According to Harms and colleagues, an extraperitoneal approach should result in fewer operative complications.

© Mr Gavin Holt :: CotswoldClinics.com :: Print this frame